Like just about everyone last week, we were watching the news about GameStop (GME) and the role Robinhood traders played in the market. In light of Robinhood’s disabling of buying in a number of stocks, there is a lot of fury about potential conflicts of interest that are not new but now suddenly in the spotlight.

The situation emphasizes the need for transparency in markets and why certain marketing that appears beneficial – “Trade stocks for free!” – may have deleterious characteristics under some circumstances.

Matthew Trudeau, chief Operating Officer at ErisX, has participated in the successful launch of 12 electronic trading venues. Prior to ErisX, Matthew was most recently co-founder and president of Tradewind Markets, an electronic trading platform and blockchain-based post trade system for physical precious metals.

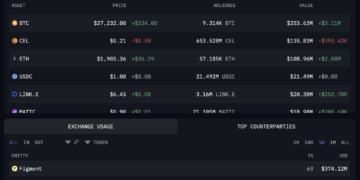

In a practice known as “payment for order flow,” or PFOF, brokers sell their clients’ order flow to professional trading firms called “internalizers.” This practice has been covered by the media many times over the years, more recently by Institutional Investor and MSN. Brokers send individual investors’ orders, e.g., to buy stock in GameStop, to the internalizers that pay to trade against this “dumb flow.” The internalizers then net-offset the retail trades, keeping the spread, or offset trades on the national stock exchanges, presumably at a profit that exceeds the cost of their payments made to Robinhood and other retail brokers. The majority of retail equities orders never execute on an actual stock exchange.

So, retail traders trade for “free” and the brokers and professional internalizers still make lots of money. Not all market makers support PFOF. The question retail traders should be asking is, how much in hidden fees are they paying? If the non-transparent markups, spreads, or opportunity costs are greater than an explicit and transparent trade commission, then “free” may be pretty misleading. How fees and conflicts are disclosed and managed, or not, is pretty important. The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) seems to agree.

Well, good thing this only happens in equity trading. Crypto must be free of these conflicts, right?

There is a lot of lip service paid to “democratizing access.” Call us fundamentalists, but when we envision a “democratized market” we envision an exchange where all members can trade with all other members according to a common set of rules and standards.

If the non-transparent markups, spreads or opportunity costs are greater than an explicit and transparent trade commission, then ‘free’ may be pretty misleading.

It’s a market where price discovery and liquidity are available to all on equal terms, and where the commingling of order flows from many different participants with diverse market outlooks and time horizons produce a better market quality. A central limit order book (CLOB), the model most typically found on regulated futures and stock exchanges such as the CME and Nasdaq, provides such a market structure (as we discussed here and here). On a CLOB, with a published price schedule and displayed quotations, the full cost of a trade is explicit and transparent: the price at which investors can purchase or sell a quantity of an asset plus the transaction fee. It is really pretty simple.

See also: Jill Carlson – The GameStop Stop Is Not a Technology Problem

It does not strike us as very “democratic” when order flow gets channeled to exclusive liquidity providers that gain an informational advantage as a result of that exclusivity, particularly where that conflict is not well disclosed. Almost without fail, if a trading or pricing arrangement is not fully transparent there is, at worst, a problem or conflict. Or, as may be the case with unregulated/offshore markets, something untoward may be happening. At best there is an arrangement the parties would rather keep quiet from their products, er, customers.

As a new asset, crypto has had the opportunity to learn from the market structure examples of traditional markets. Unfortunately, some of the lessons that have ported over are sub-optimal arrangements rather than best practices.

An apparently significant part of the crypto market structure involves brokers sending client orders to over-the-counter “trading venues,” in that model a synonym for internalizing dealers. Or, in some cases, the broker is the dealer. (It is worth noting that in traditional markets there are strict rules that generally prohibit or restrict exchanges and brokers trading against their own clients.) OTC liquidity provision is a variation on the PFOF model. Instead of all-to-all trading with the explicit and transparent fees CLOBs enable, the OTC liquidity model replicates the implicit costs, informational advantages, opacity and potential conflicts of interest that have been problematic in equities and FX trading.

See also: Preston Byrne – ‘The Squeezening’: How the GameStop Backlash Will Curtail Freedom

The Robinhood saga also exposes another risk of the exclusive liquidity provider model: counterparty risk. There has been a lot of speculation about why Robinhood disabled the buying of certain stocks. We will not wade into that discussion, but it does beg the question of what happens when the liquidity providers cannot or will not provide the liquidity, or cannot or will not settle trades. A CLOB diversifies counterparties and a clearinghouse eliminates settlement risk. These are proven market infrastructures that were designed in response to past market failures and disruptions.

In summary, while it has been both exciting and disheartening to watch the Robinhood and GameStop spectacle, we have yet again been reminded of the importance of well-designed market structure, understanding the risks and potential conflicts, and aiming to remove them explicitly and transparently. Crypto markets can be all-to-all, which is, in our view, closer to the democratized access that so many claim to want and/or offer.

Credit: Source link