Peter Martin, Visiting Fellow, Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University.

The West is arraying financial weapons never deployed before against a country of Russia’s size, forsaking some of the principles that have defined it.

Part of what has defined the West – and most of what has been the world’s engine of prosperity for the past century and a half – has been the free flow of goods across borders, a working banking system, and property rights.

There’s been an implicit understanding that no sizeable nation (Russia’s economy is about the size of Australia’s) would be denied access to these things. Otherwise the financial system wouldn’t be the financial system.

That seems to have been the understanding of Russian President Vladimir Putin. But now, the West did the unthinkable, and the global financial system may never be the same again.

Russia’s vast war chest

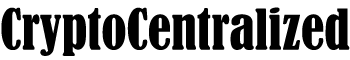

Over the seven years since Putin last invaded Ukraine (and annexed Crimea) in 2014, Russia’s central bank has almost doubled its holdings of foreign currency and foreign bonds and gold, building up a reserve of USD 630bn at a considerable cost to the living standards of ordinary Russians.

It was a war chest that would enable Russia to continue to buy things that could only be bought in foreign currency, even if customers overseas refused to trade with it and supply it with that currency. It was Russia’s insurance policy.

And although it could have been stored in Russia, much of it was kept in banks in the UK, Western Europe and the US, for easy access when it was needed to buy things on those markets.

Whatever his other suspicions of the West, Putin seemed to think its financial system wouldn’t be turned off – not to a nation of Russia’s size.

China will learn from Russia’s mistake

On February 27 the West froze the assets and travel of named oligarchs and Russian officials, as was expected.

Also, and less expected, it stopped named Russian banks from accessing the messaging system used to transfer money across borders, ensuring they were “disconnected from the international financial system”.

And, much less expected, it froze the reserves of Russia’s central bank stored in France, Germany, Italy, the United Kingdom, Canada, and the US – the hundreds of billions of savings legitimately placed in foreign banks for safekeeping.

That action broke the bond of trust that makes a bank a bank. And while effective – Russia can’t get access to hundreds of billions of foreign dollars it has painstakingly built up to buy supplies and support the ruble on currency markets – it can only be done at this scale once.

China will have taken note and won’t be entrusting any more foreign assets to banks in France, Germany, Italy, the UK and the US than it can afford to lose.

Freezing foreign reserves has been done before – but only to the less powerful nations like Iran, Afghanistan and Venezuela. This is the first time it’s ever been done to a member of the G20 or the UN Security Council.

The battle of the fridge vs the TV

The ruble has collapsed 40%. Denied access to the foreign currency it would need to support the ruble in the market, Russia’s central bank has attempted to stem the tide by more than doubling its key interest rate, lifting it from 9.5% to 20%.

The ruble falls off a cliff

Russia has blocked Russians from sending money abroad, stopped paying foreigners interest payments on government debt and required every Russian firm earning dollars to hand over 80% of them in exchange for rubles.

For ordinary Russians, there’s a “battle of the fridge versus the television”: the stark contrast between the reality of daily life against the claims of state media.

Until recently, Russian TV wasn’t even using the word “war” (although it has started). The television has been telling Russians things are normal.

But Russians’ fridges, ATMs, and their blocked Visa, Mastercard and Apple Pay accounts are all telling them something else.

From buying a washing machine to getting a mortgage, an awful lot is suddenly expensive or unavailable. But official polls (for what they are worth) show public support for the “special military operation”. Television has been using the realities of shortages and price increases to attack the West for becoming anti-Russian.

Hitting Russia’s elite and military where it hurts

Whatever ordinary Russians actually think about the war, the impact of the West’s unprecedented sanctions on the Russian elite is likely to matter more. No longer able to travel aboard, access their offshore savings or pay the school fees of their children abroad, the oligarchs have at least the potential to exert influence.

The final way in which the financial embargo might succeed is by starving Russia of foreign exchange to the point where it can’t buy spare parts for its military or the computer chips and other materials needed to make those parts.

There’s every chance none of these will work quickly, every chance they will further impoverish Russians, and every chance that, if Russia subjugates Ukraine, the West will find the sanctions impossible to withdraw without losing face.

The global financial system changed when the West did the barely thinkable on February 27. It’s hard to see a way back.![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Credit: Source link